- Additional context

- Person or institution

- Primary source

The Faculty spent the evening of Monday March 15, considering the question of Registration. To bring the group together in friendly fellowship we served an informal supper before the meeting, and twenty-seven members of the faculty were present--of whom eleven were Chinese. Fourteen of us had attended the College Conference and were more or less familiar with the general problem. We tried to face our particular problem--what Ginling should do to meet the government requirements, what the consequences would be if we could not satisfy them, etc. etc. To add in starting discussion, Mrs. Thurston, Miss Hoh, and Miss Spicer, who had represented Ginling at the Council of Higher Education, and Miss Hanawalt who was on the Business Committee of the College Conference, had prepared the following questions:

- Do you think Ginling should modify its aim and purpose to satisfy Clause 5? Is the government justified in putting in such a clause?

-

Do you think that they should be given up in order to be registered?

-

What would your opinion be if the responsibility was with you?

-

What would be your attitude if there were a Chinese majority in favor of registration?

-

Mrs. Thurston made a statement in regard to Registration as it had been under discussion in East China for ten years. The decrees of 1917 and 1921 were read and the efforts made by certain schools to secure registration were reviewed. The local situation in Hangchow, where schools have been registered under friendly officials, and the case of Nanking officials stamping diplomas in several girls’ schools last June were reported. The steps to be taken by Ginling in order to conform to Regulations 1-4 were traced and the action of the Executive Committee urging uon Missions the choice of a Chinese representative on the Board of Control was approved by vote of the faculty who expressed themselves in favor of meeting these four requirements “as quickly as possible, even though the revision of the Constitution be involved.”

(Regulations 1-4 require that the term “privately established” be prefixed to the official name; that the president or vice-president be Chinese and represent the institution in applying for recognition; that a majority of the Board of Control be Chinese. Regulation 5 is translated “The institution shall not have as its purpose to propagation of religion” or as Dr. Timothy Lew puts it “religious proselytization”. Regulation 6 is in two parts (a) “The curriculum of such institutions should conform to the standards set by the Ministry of Education” and (b) “It shall not include religious courses among the required subjects.”)

All discussions centered on Regulation 5 and the second part of Regulation 6. We tried to limit our discussion to the particular problem which Ginling is facing. Some questions asked by persons without general understanding of the background led us off into somewhat wider questions such as general attitude of other Government toward private schools founded by religious groups, suggested by one question “Is the government justified in putting in Clause 5?” Toleration of Jewish and Parochial Schools in America, the failure of Oregon to eliminate the private school were cited; also the fact that England not only tolerates but makes grants to such schools and includes religious instruction in her Board School course of study.

The direct question “Are we willing to surrender our aim to be registered” as raised by Mr. Djang Fang. The fact that our aim as a college is “higher education under Christian auspices” was brought out but the statement that Gining was founded “for the furtherance of the Cause of Christ in China” has been made in all our catalogs and would probably be challenged if Clause 5 means what it would seem to mean. Miss Spicer and Miss Treudley suggested that a statement of the college aim in educational terms instead of the Founders’ purpose in religious terms need not be denying our Christian aim. Mr. Thomson questioned whether the present statement represented our present aim and if so whether it would be honest to restate.

Mr. Djang Fang felt that the Government was trying to force Christian schools to change their aim; that if we reworded it they would not be satisfied. Miss Hoh and Miss Griest stated that the Chinese delegates at the College Conference did not so interpret Clause 5. Miss Hoh brought out the need felt by China to prevent political propaganda in foreign schools; that Peking Chrisitan Educators say “Don’t force the exact definition of Clause 5 because Clause 6 shows that Christian teaching is allowed.” Miss Treudley said we might state our purpose in a way to avoid giving offence to people who disagree with us and yet state it as both educational and religious. As long as we are honest in our main purpose--Christian Education--we can only state it as our aim. Otherwise we cannot register and be honest. The possibility of having our honesty questioned by government inspectors after registration was mentioned and also the possibility of later demands which could not be met being made by the Government and cases in Japan were cited. Miss Hoh thinks there is no need to fear that China will do as Japan did--that if we register we shall have support of educators and be in a better position to fight for liberty.

Miss Spicer and Miss Treudley brought out the point that the decision to register would be made by a Board of Control with a Chinese majority.

The question of required vs. elective courses in religion was brought in and Mr. Thomson expressed the opinion that it ought to be decided on its merits apart from the question of registration. The difficulty of faculty deciding for students and the chance that students would incline to choose registration even at the cost of religious courses were points to be considered. (Spicer and Hoh). Mr. Djang Fang said that as a Chinese citizen he would like schools to be registered and he was willing to reconsider the religious program but not just for the sake of registration. He felt that the advantages of registration were not very great. A few graduates might get government scholarships. Better feeling between Christian and government schools might result but it would come in time as our schools were better understood. He admitted that “religion” cannot be taught--it is a matter of experience but that the teaching of religion could help toward religious experience. Our schools are now propagating religion we can teach boldly; if educators teach religion in a disguised way the government can criticise us. Missions ought not to be afraid. Most of the trouble is made by sub-freshman. Parents send children to Christian instead of government schools (“Sorry but a fact”). We had better get far away from the government if we want to maintain Christian influences. (“I may be a traitor to government and country but it seems to me the right position to take”)

Dr. Jones brought out the point that academic as well as religious freedom was involved; that Chinese Christians in the next generation might look back on us as betraying a trust if we yielded too easily. Opposition will soon be overcome if it is possible to go on without being closed at this time. Miss Grabill felt that we do not want to evade whatever we do, but to stand and explain our position if we have to.

Miss Hoh referred to a mandate issued recently which stated that schools would be closed if they failed to apply for registration. Mrs. Thurston told of a recent interview with a Kiangsu official who was asking about this mandate and replied that they had no intention of closing the Christian Schools; that they knew they were good schools and sent their children to them--that in 1917 and in 1922 no action against schools was taken by the government; that everyone thought the recent mandate a sop to the communist group who oppose registration of Christian schools on any terms. Miss Hoh felt that there might be some danger of government action this time. Miss Loh thought that we should know how to hold our aims and unless we changed them we should not compromise. If the aim was right there was no need to change it. In the near future she did not feel it was a matter of great importance. Miss Loh thought it was a chance for Christians to prove whether they hold their aims firmly or not. China has a constitution in which each citizen has freedom of religion. We might be refused registration because we are weak in Chinese.

Miss Case and Miss Treudley brought out the position held by the majority of Chinese in the College Conference as being different from Mr. Djang Fangs in favoring registration and in feeling that the Government did not wish to push out Christian Schools.

Miss Whitmer asked about the report of the commission appointed to discuss the terms of registration with the Peking Ministry of Education. Mrs. Thurston stated that the present minister was not as friendly as the one who issued the Regulations; that the Commission would wait for a favorable time and make an informal presentation--”Conversations” on the subject, stating among other things the difficulties in connection with supporting constituencies abroad. Miss Griest stated that schools in Mexico were not allowed to teach any religion--not even voluntary Bible classes but that Missions were opening new schools and admitting the need of freeing the government from the grip of the Catholic Schools against which the regulations were issued. A similar situation existed in Japan. Miss Hoh argued that Peking used the Bible as a text in English classes, that religious work could be done in elective courses and through personal work, giving students freedom to choose to become Christians. Government has no right to prevent teaching. She pointed out the difficulty of getting Chinese Christian opinion because there was as yet no Chinese Church,-only missions.

Reference was made to a discussion last spring of the question of required courses of religion in which faculty opinion was strongly on the side of requirement on grounds similar to those on which History is required. Miss Griest stated her position to have been in favor of required religion courses for the intellectual foundations of belief but that the arguments of the Chinese at the Conference had influenced her and since they were representative Christian men and know the Chinese better than we, she would be in favor of re-opening the discussion of this point but did not think we ought to register on that basis. Miss Spicer felt that the criticisms made were of a required system as it had been worked and Mrs. Thurston pointed out that some of them were criticizing middle school and not college teaching. Several of them had taken their college work in America. Miss Loh admitted that any required course was likely to be less popular and more interest was taken in electives. Miss Spicer felt that required work in college was advisable but if the field is over by work done in Middle School, College Freshman would not elect religion.

The question of making report to students was discussed and faculty judgement as to how it should be discussed with student groups. This was left to the Advisory Committee to arrange and they have asked the committee who prepared for the faculty discussion to plan for informal conferences with seniors and juniors.

In the early 20th century, Christian schools were largely free of government regulation. In 1913 and 1917, the Chinese government issued requirements for the registration of private educational institutions. Many colleges, however, ignored official Chinese recognition and instead maintained charters under American organizations. As Chinese nationalist movements (which were often anti-colonial and opposed to the presence of proselytizing foreigners) gained steam through the 1920s, registration became a more pressing question.

Registration required a majority of Chinese faculty.

Matilda Calder Thurston, the founder of Ginling College, was an American missionary who moved to China in 1902. She spearheaded the college’s activities as the institution's president from it beginning in 1918 until 1928.

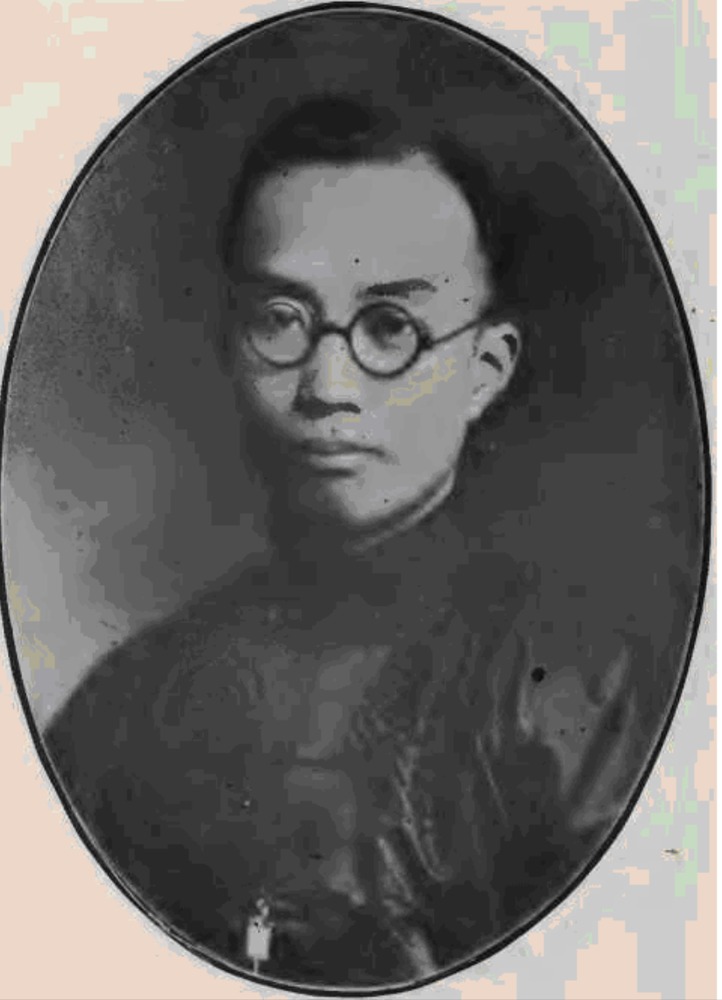

Phoebe Hoh, a prominent faculty member of Ginling pictured in the top row, right-hand side. She played a large role in beginning the rural service center and worked at Ginling’s first center in Sichuan at Renshou (Jenshow) beginning in 1938. She received her A.B from Ginling and her A.M from Columbia.

Eva Dykes Spicer (1898–1974) taught at Ginling College from 1923 to 1951 under the auspices of the London Missionary Society. Spicer was one of the very few non-Americans on the foreign faculty at Ginling. Spicer’s background was not that of a typical missionary. The daughter of a solidly middle-class, even wealthy, family, she was educated at socially elite and expensive private schools. In 1917 she went to Oxford, where she studied history at Somerville College. At the university, she was an active member of the Student Christian Movement and, in her final year, was elected Senior Student of her college. Almost immediately after graduating in 1920, she wrote to the secretary of the LMS, inquiring about opportunities for missionary service. After teacher training at the London Day Training College, later the Institute of Education, and a spell at Mansfield College, where she took courses in pastoral and teaching work, she left for China in August 1923. She had been appointed to teach religious studies and to assist in directing religious activities at Ginling College in Nanking.

Ella M. Hanawalt was a professor at Ginling College from 1921 to 1926. There she established a training school for high school teachers, many of whom later followed her to the United States for higher education. Miss Hanawalt was born of Swedish-American background in Knox County, IL. She attended elementary and high school in Galva, was a student at Knox College for three years, and then transferred to the University of Michigan, where she obtained her B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. degrees. She had additional graduate work at the Universities of Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the University of Nanking Language School. She is also a graduate of the Scarritt Bible School.

Clause 5 translates: "The institution shall not have as its purpose to propagation of religion."

This question with its multiple parts—the larger question about the desirability of religious courses, the educational value of learning about religion, the status of the college as a missionary enterprise—frames the entire discussion summarized in this document.

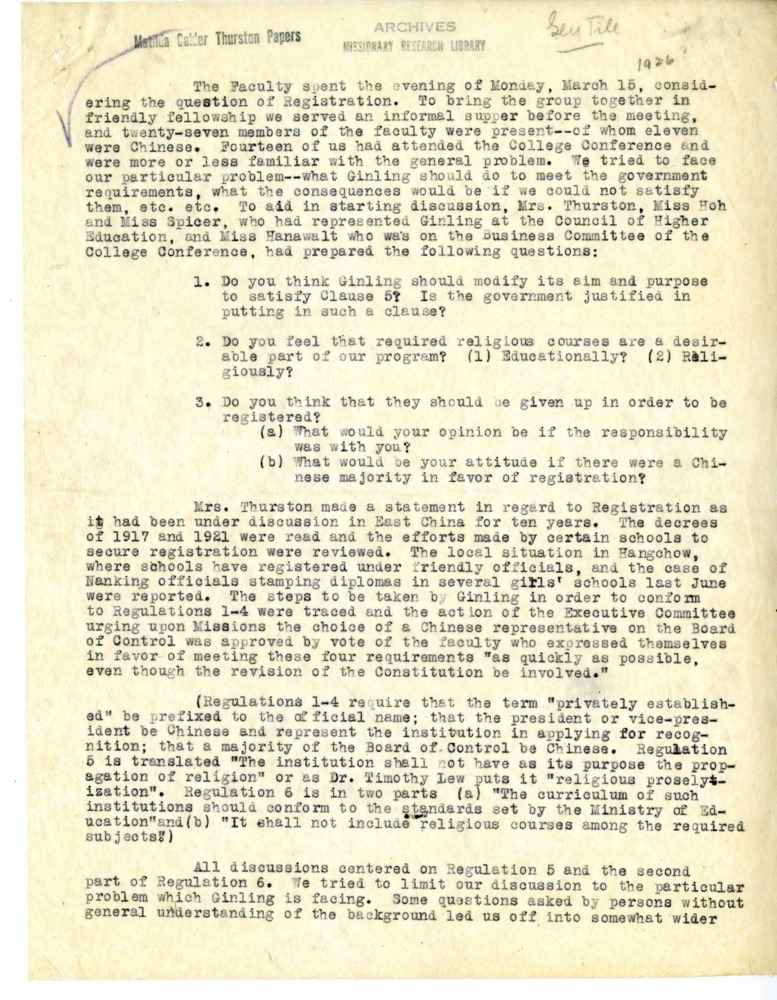

This document illustrates the altered curriculum requirements from September 1927, in the aftermath of the meeting described in the present document. Religion curriculum was cut from 14 required credits to 8, all of which were now electives within the department.

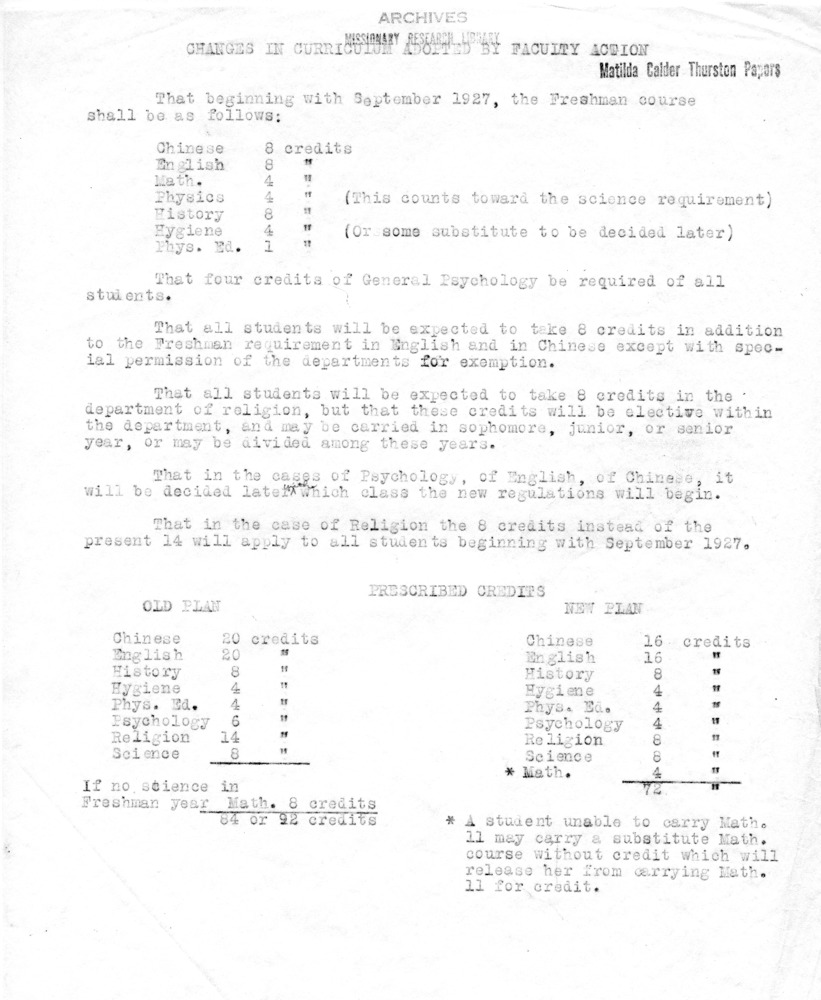

This document details the result of a vote on changes to Ginling College's religious curriculum, with results sorted by ethnicity of voting faculty. Interestingly, one faculty member chose to vote "unclassifiable" instead of yes or no, citing that they disapproved in light of the majority view of Chinese faculty against requiring 8 elective religion credits.The document also includes information on when religion was an available major, and department course lists sorted by required and not required.

The acting president at this time, Matilda Caulder Thurston, left her position as a result of the registration requirement that the president of registered colleges be Chinese. Wu Yi-Fang assumed her position in 1928. This document contains Thurston's farewell address.

For further information on this topic, see the exhibit "A Tale of Two Presidents"

Timothy Ting-fang Lew was born in Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China, in 1891. Dr. Lew received his preliminary education at St. John’s University, Shanghai, then went to America and entered the University of Georgia. He later distinguished himself at Columbia University where he received the degree of Bachelor of Arts (1914), Master of Arts (1915,) and Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology and Education (1920). He then studied Theology in the Union Seminary and later received from Yale the degree of Bachelor of Divinity in 1918.

He returned to China in 1920, and was appointed dean of the Graduate School of Education, Peking Government Teachers’ College and then professor of Psychology in the National University of Peking and member of the theological faculty of the Peking University (Yenching Ta Hsu’eh). In 1921 Mr. Lew was elected dean of the School of Theology in the Yenching University, resigning his deanship in Teachers’ College.

In 1922, Oregon voters approved an initiative mandating public schooling for the state's children. Support for the bill was motivated by a variety of political visions, including a nativist surge that sought to "Americanize" recent immigrants, particularly Jews and Catholics—the Ku Klux Klan, for instance, made mandatory public education part of its political agenda. In 1925, the United States Supreme Court ruled the bill unconstitutional in "Pierce v. Society of Sisters."

In her farewell address, Ginling College founder Matilda Caulder Thurston elaborates on the original religious mission of Ginling College, and how that mission had changed over the course of her tenure.

Mr. Djang Fang was a Reverend who was on the Ginling Board in 1927. He was a member of the Band of Evangelists supported by the Blackstone Fund, which was a group of secen men who distributed copies of the Gospel, pamphlets, and other evangelical papers.

The theme of rebranding a religious mission into a mission regarding education about religion reappears.

Miss Rebecca Walton Griest graduated Wellesley in 1912 and taught history at Swarthmore from 1913-1914. She arrived at Ginling in 1919 where she taught English for three years and then taught history from 1924-1927. In between those two positions, Miss Griest took two years off to study at Columbia. Upon her ultimate return to the United States, Miss Griest sat on Ginling’s Board of Control.

The value of classes in comparative religion or religious studies was debated across Chinese schools throughout the 1920s. Chinese leaders and activists who had been educated in the United States, particularly at Harvard and Chicago, had taken courses in comparative religions. in 1922, the president of Peking University called for the creation of a religious studies discipline within the humanities that would replace Christian education at missionary colleges. The suggestion met with anger from Christian educators, many of whom felt they had been working in religious studies for years. The debate over religious studies in Chinese higher education was significantly shaped by western education norms, even as it figured in Chinese nationalist, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian movements.

This comment reifies a clash between government interests and school interests. It makes allegiance to one or the other zero sum—to be for Christian education here is to be against China.

Miss Ada Grabill was a graduate of Oberlin College and was likely involved in the music department at Ginling. She played the wedding march at a Ginling wedding and wrote an article for one of the Ginling College Magazines on “The Recent Development of Music Study in America.”

Miss Loh Zung-nyi (陆慎仪, 1900 -1981) was born on March 10, 1900 in Kiangsu, China. She attended Ginling College in 1920-21, then transferred to Wellesley in 1921, where she graduated in 1924. In 1925, she received her Master’s in Mathematics from Cornell University, and then returned to teach at Ginling from 1925 -1931 and from 1946-1948. She was also the Acting Dean of Studies during 1946-47. Miss Loh used her mathematical expertise to become a founding member of the Chinese Mathematical Society. She returned to America in 1948-1949, where she taught at Wellesley. She went on to teach at Smith College, Wilson College, Western College and Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. She died on April 25, 1981. In her will, she created a fund, the Louise Zung-nyi Loh Memorial Scholarship Fund, which provided scholarships to students with an interest in East Asia Studies at Ohio State University.

Miss Emily Case served as Ginling’s Director of Physical Education. She was a graduate of Wellesley College’s class of 1921 and worked at Ginling from 1923-1927 in the physical education and hygiene departments.

Miss Harriet Mildred Whitmer (1885-1976) was born in 1885. She received her Master’s at University of Michigan in 1917. In 1924, she went to Ginling in 1924, intending only to become interim head of the biology department there for one year while another professor took a year off. However, Miss Whitmer ended up remaining in Ginling for an extra twenty-three years, until 1948. In 1941, she received the Second Prize of Achievement from the Chinese government. After Japan surrendered in August of 1945, Ginling students and faculty were eager to return to Nanking from Chengtu where they had their wartime campus since 1937. However, the Nanking campus was severely damaged by the Japanese occupation that began in June of 1942. After Japan’s surrender in 1945, Miss Whitmer joined the rehabilitation effort led by Dr. David S. Hsiung so the campus could re-open in September of 1946. She left China in 1948, followed by two years of missionary work in Malaya. After her retirement, she spent five years in Chicago with the Midwest Chinese Student and Alumni Service, which reunited her with thirteen fellow Ginlingers.

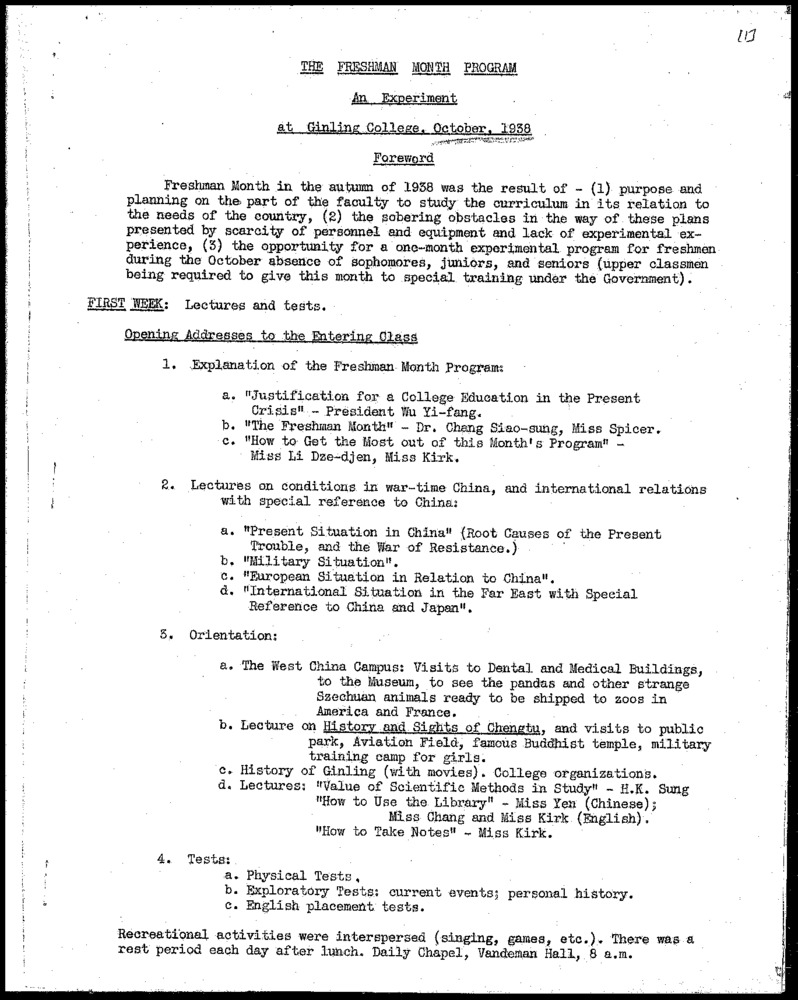

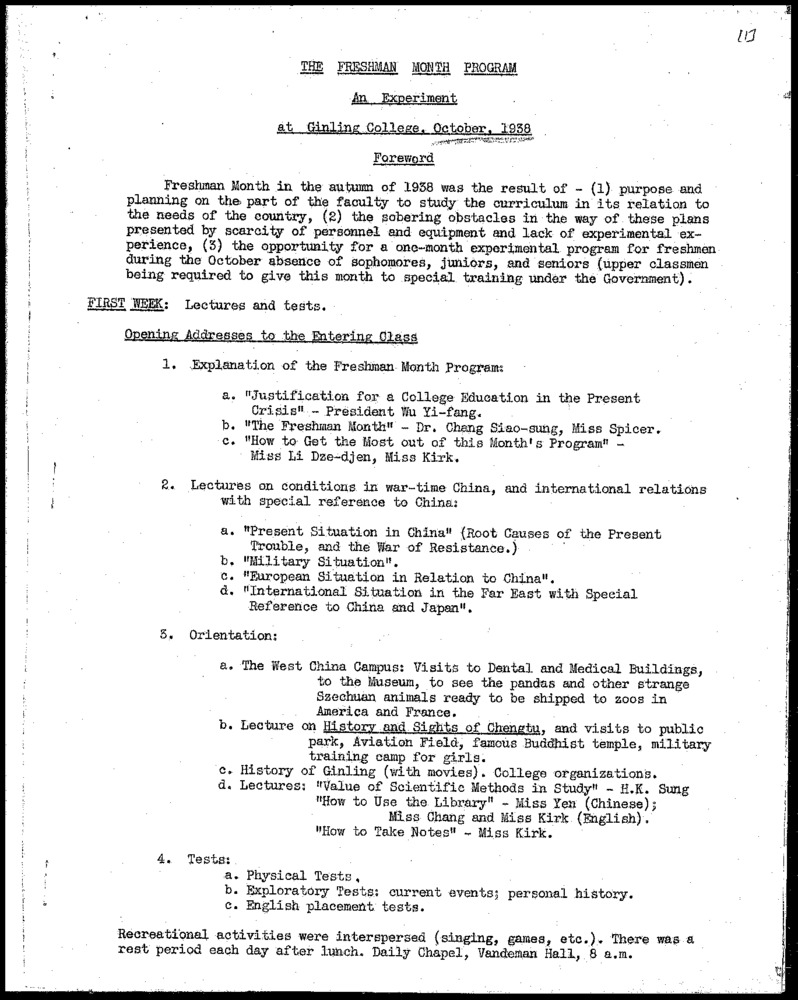

This document contains accounts of a month-long orientation program for the 1938 fall semester. In it, the students visit different religious centers in Chengtu. They visit Buddhist, Muslim, Taoist, and Catholic worship sites, but not Protestant ones. This fact, coupled with the commentary on their visit to the Catholic church, demonstrates how the sometime fraught relationship between Protestantism and Catholicism trickles down into the consciousness of Ginling students and faculty.

The argument is made here that religious courses serve an educational purpose. It suggests a hesitation to doing away with religious courses, arguing instead for a reframing of their purpose.

This argument from 1927 continued to shape Ginling's curriculum for decades. The 1940s rural service programs, which offered educational and social programs across rural villages, included religion classes alongside those teaching domestic and vocational skills. Instead of shaping the program as a primarily evangelistic enterprise, the religion classes existed as one component of a larger program in which they were framed as valuable to a person's character and knowledge of the world.

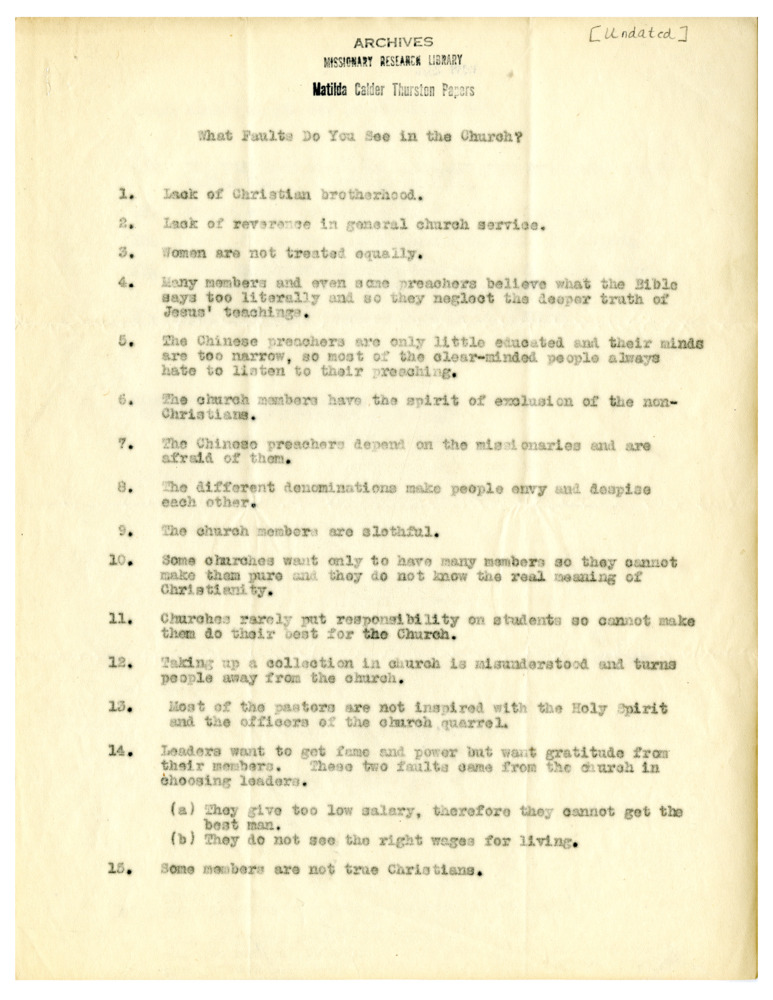

This document includes a list created by students of the faults they see with Christianity. Likely dating to 1922, this document demonstrates the basis of the faculty members' fears about students losing touch with religion if the subject were not mandatory in the curriculum.

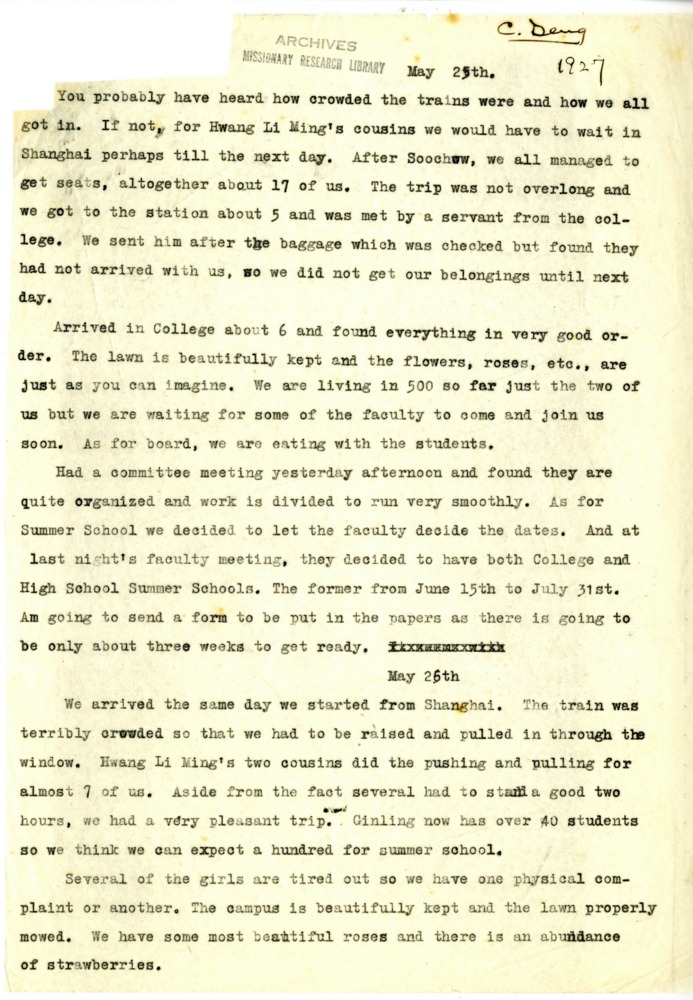

This document is a series of letters written by a faculty member in 1927. She discusses the changes in chapel programming and the wishes of the student government to maintain a level of secularity and to protect religious freedoms on campus. This document gives insight into student perspectives on changes in religious practice during the period of religious transition that accompanied government registration.